There is Something Fishy in This Picture

A fisherman stands thigh deep in a crystal-clear mountain fed stream. He casts, sending his line to softly settle on the stream surface. The fly, an imitation of an insect, floats enticingly, daring any hungry trout to rise and strike.

Strike the fish does. A dance follows that during the fishing season is re-enacted thousands of times throughout New Zealand. Sometimes the fish is clever and strong enough to escape, while other times it will be netted and brought to shore. Most likely he or she will be released, but if of a good size, the fish may have its photo taken first. Occasionally the fish will end up on a BBQ.

This dance, fisherman and fish, is enjoyed by thousands of anglers each year (but doubtfully by the fish).

Today we tend to think of this country and trout in the same thought. The scene described above is somehow quintessential New Zealand. It has not always been like this.

American author, Zane Grey, made trout fishing in New Zealand famous.

Early photos from the 1920s show him holding huge trout, trout that weighed over 20lbs, the likes of which are now never seen. How did they get so big?

It may surprise many people to learn that Brook Char, Rainbow and Brown trout are not native to New Zealand. Brown trout were introduced in the 1860s, Brook Char in the 1870s, while Rainbow trout were introduced in the 1880s. All in their home environments are apex predators.

Like Lions, they are predators at the top of their respective food chains. Native fish did not stand a chance.

Trout fishing in the Rangitikei River

New Zealand’s Native Fish

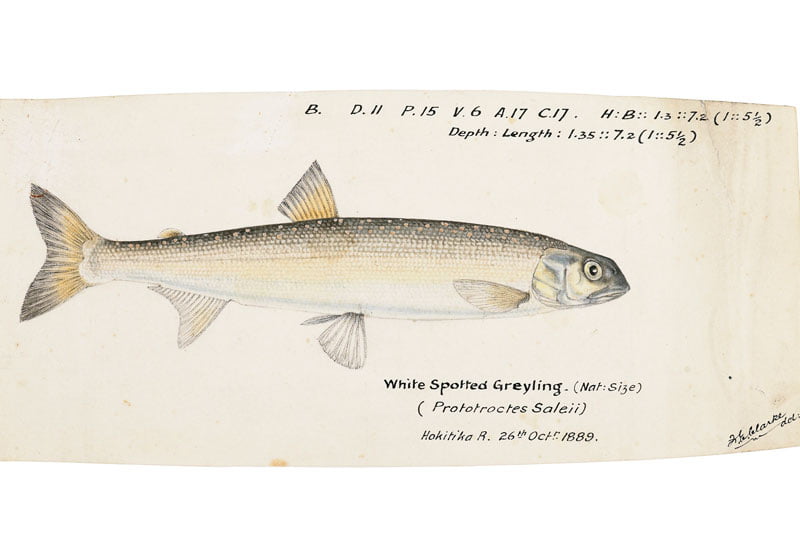

New Zealand has 58 native species of freshwater fish. Most of these fish, with several exceptions, are small and seldom seen. Two-thirds of them are threatened with extinction. One has already gone extinct. None of them until the late 1800s had ever encountered a voracious predator such as trout. For the Grayling or Upokororo, our only native vegetarian fish species, this encounter, associated with habitat destruction due to widespread forest clearance and possibly some other unknown cause, was terminal.

No Grayling has been seen since 1939 at the latest.

Most of our native fish come out to feed at night, hiding under boulders, banks or logs during the day. Being shy, small, well camouflaged and rarely seen, they do not generally enter our consciousness.

This habit of shyness may be fatal.

The New Zealand Grayling is now extinct

A New Zealand Delicacy

A seasonal New Zealand delicacy is whitebait. Whitebait are the juveniles of five different galaxiid species. The adults live in either mountain or lowland streams. The spawning habitats of most species are little understood, but the result of those spawning habits are shoals of juveniles entering rivers and streams at certain times of the year. Whitebait season as it is known.

But those shoals are smaller than they used to be. Again, many factors come into play, but the most likely cause of their reduction is poorer water quality caused by agriculture, and plantation forestry.

Of the five species that constitute “Whitebait,” three are endangered. There is plenty of finger pointing about who is responsible, but little overall action.

Whitebait – A New Zealand Delicacy

The Longfin Eel

Imagine a native fish that once 20 years old, or older, swims across the Pacific to Tonga to breed. A fish that often grows to metres in length and can live for 70 or 80 years. This unique fish is our endemic Longfin Eel. It is less numerous than the more widespread Shortfin Eel which is found throughout much of the Pacific. Both species of Eel may be taken under quota or fished recreationally.

The Longfin Eel is classed at risk with its population declining. So how come it gets fished commercially?

Are We Doing Something?

So, with all the above you would think that we would be working hard to protect our native fish species. We would have tougher rules around riparian zones, about the leaching of nutrients into waterways from agriculture, about limiting riparian damage. Maybe we should also be eating more trout, not just letting them go!

The Clanger

The clanger, the complete dichotomy, is that in New Zealand we only formally protect two species of freshwater fish. Those two are the introduced trout and the Grayling. A bit too late for the Grayling as it was already extinct when it got protected. The protection of Trout has more to do with strong lobby groups, traditions and money than any environmental reasoning.

How many more species are to follow the Grayling before we get serious about protecting this part of our natural heritage?

Brian Megaw